In this series, over the next several months, we will be sharing artwork and brief writeups of the creative process, from our Linked Descendants working group members.

Some of us have begun to explore our thoughts, feelings and the multi-layered experience of finding our ancestors, through collage work. We created collages on our own using a specific framework as a starting point (eg: a river of life, an explosion of awareness, a tree of knowledge or life, a path towards or away, etc.) and then shared with each other in small breakout groups. Most of us found this to be a powerful way to further process our often conflicting emotions. Expressing what we know in visual, rather than written terms, allows for increased awareness, deeper insight, and further integration of the new and/or more difficult truths around our ancestors and overall family histories.

Today’s collages and process descriptions are generously shared by Leslie Stainton, Cossy Ksander, Cindy Carroll and Martha.

THE SCARLETTS

- Frank D Scarlett by Leslie Stainton

- Fanny Scarlett by Leslie Stainton

- Francis Muir Scarlett by Leslie Stainton

I made these collages after more than a decade of researching and writing about my enslaver ancestors, the Scarletts of Glynn County, Georgia. During that time I’d uncovered a lot: ads to purchase enslaved “Negroes”; ads to track enslaved men and women who’d fled Scarlett plantations; shipping manifests for runaways who’d been caught and jailed; an account of my great-great-great grandfather’s purchase of an enslaved African from the illegal 1858 slaver The Wanderer; correspondence documenting the escape of two-dozen enslaved people from my family in 1862; a “Freeholders’ Agreement” from 1868 dictating the harsh conditions under which freed African Americans were to work and live on Scarlett lands after the war.

I’d written plenty about my forebears and thought I knew how I felt about them—a jumble of shame, horror, bewilderment, pity. But it wasn’t until I set out to render my ancestors visually that I realized the depth of my contempt for three individuals in particular: my great-great-great grandfather Francis Muir Scarlett (1785-1869), the patriarch of the Scarletts, who for reasons I’ll never understand steered the family into the slavery business in the first place; his oldest son, Francis Dunham Scarlett (1814-1897), a man who hunted down runaways and fathered at least one mixed-race child, probably more; and Francis Dunham Scarlett’s wife, Fanny (1830-1863), an imperious plantation mistress who espoused Christian piety while questioning the “depravity” of the enslaved men and women who dared to run away from her.

As I worked, I found myself slashing at their faces. I soon realized that my hand grasped what my mind had not yet acknowledged: I wanted, at some level of my being, to obliterate these people.

My collage was a standard, hand-drawn genealogy of the first 4 generations of Veatches, mostly in Maryland. I noticed a few things through the exercise: 1) The brightly colored sticky notes loosely attached to the generational chart, accurately represent the loose affiliation of enslaved and enslaver. The names stand out, but can also be torn away or re-arranged at any moment. 2) The half-dozen or so named, enslaved people in each family must represent only the house staff, because all the Veatches were growing tobacco and would have had many more enslaved people working in the fields. 3) I’m particularly upset that these ancestors bear my maiden name AND participated in the usual economic system of their day; that Elizabeth Masters Goslin was fervently Christian AND held slaves; that Ninian Veatch’s will expressed deep love for his daughter AND expressed it by offering the labor of enslaved Tobey to insure his son’s compliance in caring for her. 4) I feel a shamed relief, noticing that, by the fourth generation, all of the named, enslaved people belong to cousins, not to the direct-line ancestors. (Because the direct line went bankrupt growing tobacco and had to leave town, re-appearing in South Carolina just in time to die in the 1780 Battle of Camden!)

— Cossy Ksander

.

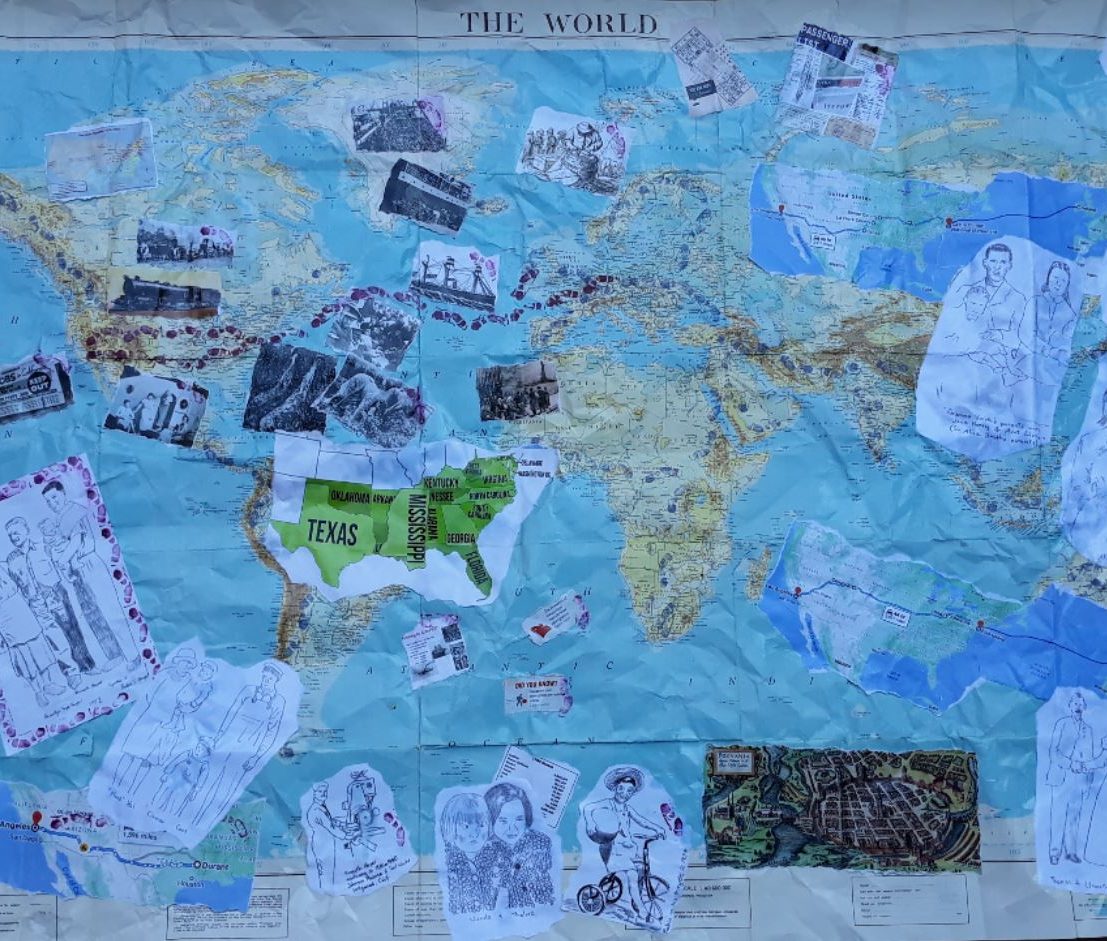

FOOTPRINTS

I started putting the footprints of the two branches of my family’s emigration routes from Europe to the US against a world map. Then I pasted a close-up of the Sims/Smith family route from the British Isles to Virginia and through the Southern states to California. And the close-up of the Heyer family from Germany to Pennsylvania, and across the US to California. Means of travel on steam ship, wagon train, and railroad made sense to add. The Sims/Smiths were sharecroppers and farmworkers who picked cotton for cash, so there are a few photos of the long cotton bags they had to fill. When my mother was a toddler during the early 1930 Dust Bowl decade, she was brought to the fields with them and ordered to sit on the end of the bag and never leave so she wouldn’t get into trouble. She told us they didn’t use lampshades then, just naked light bulbs. This is the family line that I’m told enslaved people 5 generations earlier. Despite their poverty, my Grandpa Sims got a job as a mechanic on the Southern Pacific Railroad, which shipped the family to California after WWII. There, he was able to get a loan to buy a house and lived comfortably for the rest of his life.

One thing I realized was that this exploration felt factual, distant, and impersonal. So I added sketches of the faces of the living ancestors on each side that I knew as a child.

I’m realizing that in starting with the eagle-eye view, I started too big; I need to focus. I want to explore the Mitchells, my grandmother’s great-grandparents, who are the ones who enslaved people. But I didn’t even have a picture of them when I made this collage. I’ve found out more since then, including a grainy Xerox that might have originally been a painting. I’ve started a new collage to add what I learn about the life and times of the Mitchells, who my grandmother called “the mean grandma,” because she would roll up her ankle-length apron into a rope to swat children with. I’m told they owned land in Arkansas and enslaved two people. I haven’t found them listed in the slave schedules yet though, so I have a lot more research to do.

— Cindy Carroll

.

UNTITLED

The collage was a good tool to get at the complex emotions that arise from doing this work: Awareness of advantage/privilege as a result of being the descendant of enslavers; overwhelm due to massive amount of learning and research needed to fully understand my past; feeling like a completely clueless beginner; loneliness from being the only one in my family/circle of friends who is doing this type of work. While these emotions may never subside completely, I now know they are part of the process and can acknowledge them as such when they are present.

— Martha