— By Sarah Tarr Fleming

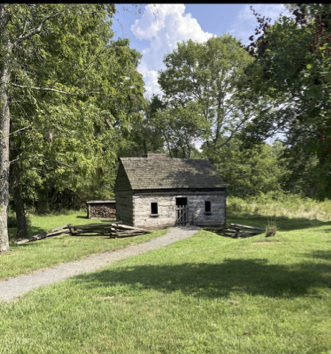

I stood in the thick green grass, looking at a slave dwelling at Sully Plantation, Chantilly, Virginia. The cabin was built to replicate one that had housed the people my ancestors enslaved. It was a hot August day in 2021, 95 degrees with Virginia’s drenching humidity. I heard the loud chorus of crickets, the leaves shifting in the nearby copse, felt the heat in the breeze.

I grew up knowing I was related to Robert E. Lee. He was my first cousin, five times removed. My father spoke of how proud his father had been to be the grandson of a Lee. Another relative wrote a book about our ancestor with very little mention of the family’s enslaved. At the same time, we all knew that slavery was an abomination but we never talked about our part in it. How did we reconcile these opposites from one generation to the next? How much emotional energy did it take to suppress the knowledge of terrible wrong doing? Does this explain our family history of depression and anxiety?

My fourth great grandfather and Robert E. Lee’s uncle, Richard Bland Lee, served in the U.S. Congress as Northern Virginia’s first Congressman beginning at age 24. Two years later when his father died, Richard inherited 29 people and 1500 acres at Sully Plantation, near what is now Dulles Airport. The enslaved were listed by name and market value. There was John of Henry (or Henry’s son), valued at 80 pounds, Sam the Blacksmith, also 80 pounds, Nancy of Prue (or Prue’s daughter), 20 pounds. There was Old Dewey, said to be “of no value,” and 25 more men, women and children. Over the next 24 years, Richard bought and sold many, many more people. For example, in 1806, he sold a man named Natt, aged 19, for $349. Later that year, he bought Rachel, her child and “their increase” for $220.

After too many bad loans to his profligate brothers, Richard had to sell Sully Plantation to his cousin, Francis Lightfoot Lee. I have to assume more enslaved people were sold then to pay off other debts. Some enslaved were taken by the Lees, first to their new home in Alexandria, then to Strawberry Vale (near present day Tysons Corner), and finally, by 1815, to the District of Columbia. In 1840, 13 years after his death, Richard’s wife reported owning twelve enslaved people. Two were adult women who probably came from Sully with her, but the rest were children under the age of ten. Who were they? Were they related to the two enslaved women, or adopted when their own parents were sold away? What happened to their fathers?

Where did the others go over the years, sold, or given away? Called property, but, actually, human souls: mothers and fathers, daughters and sons, babies, grandparents, friends and lovers; relationships not honored or protected by the grisly maw of slavery.

Weighted down by this legacy, I wandered around outside the slave cabin. I moved my feet in the grass to avoid the red ants that wanted to nip at my sandaled toes, and I kept an eye out for rat snakes, like the one curled up in the rafters inside the quarter, awaiting the rodents that come seeking food. My feelings were as uneasy as my shifting feet and wary eyes, alert to the next gut punch, the next proof of my ancestors’ cruelty, evidence of the trauma they visited on generations of their enslaved people and their descendants, and upon their own white descendants.

After my Sully visit, I flew west to Arizona to celebrate the first birthday of my grandson, Richard Bland Lee’s sixth great grandson. His older brother, Donovan, was four, the same age as Isaac, whom Richard Bland Lee sold for a shilling in 1791. I imagined my grandchild being led away forever by a stranger and I was frozen, eyes filling with both horror and tears, knowing I would have been impotent to ever nurture or protect him again. I was shocked at how disconnected I had been from a reality always facing enslaved people.

My son James had told Donovan that I had visited the family plantation at Sully. Donovan must have asked some questions because James told me the subject might come up. Even so I was not prepared when Donovan asked, after bringing me a story book for us to read, “Were the Lees bad?” I searched for a way to start the conversation about these horrors in a way that a four-year-old could grasp.

“Yes,” I told him. “They were very bad to force people to work without paying them.” He understood at once. I wondered if I were being a coward, not giving him more information. I wanted to be honest but not traumatize him with the whole story. I have the white person’s privilege to be able to moderate a conversation that Black parents don’t have when racism intrudes on their lives.

After my visit to Arizona, I reflected that maybe this is how the harms done by slavery are eased. Could this little grandson be the start of healing the damage caused by generations of enslavers and their oblivious descendants? Could the conversations that have begun to happen among my sisters and brother, my cousins, my children and grandchildren, finally break the pattern of denial?

Since beginning this writing, I have found a Black cousin whose ancestor was sexually exploited by my white ancestor. We can assume she was forced into the relationship, as he exercised his will upon her by virtue of his “ownership,” and her inability to refuse. Despite this history, my new cousin has been warm and welcoming and we do genealogical work together.

My ancestors did great damage to many, yet I remain hopeful for a future where Donovan and future generations continue the work of uncovering and acknowledging the past. Doing so can only make us all stronger.

The whispering leaves at Sully, the crickets screaming in the heat, the red ants eternally searching, and the snakes waiting, remind me of what is yet to be discovered. My family story will continue to unfold, and will now be a more truthful one.

Author: Sarah Tarr Fleming is a member of Coming to the Table, a mother, grandmother and retired psychotherapist. She lives in California. She is collecting information about her family’s history as enslavers to share with her own descendants and with those her family enslaved. She is also looking for ways to heal wounds through new relationships, memorials and reparations.

Author: Sarah Tarr Fleming is a member of Coming to the Table, a mother, grandmother and retired psychotherapist. She lives in California. She is collecting information about her family’s history as enslavers to share with her own descendants and with those her family enslaved. She is also looking for ways to heal wounds through new relationships, memorials and reparations.

Sully docent Beth Sansbury’s book, “Searching for Sully’s Enslaved,” published in 2020 provided invaluable information for this story.

©2021, Sarah Tarr Fleming. All rights reserved.

A very moving story. Thank you for sharing.