Part 1 – Finding the House, Looking for the People

At the Telling the History of Slavery conference, the woman I sat next to looked to be about my age, and like most of the attendees, not someone I knew. We introduced ourselves before the speakers began, and at the first break, shared more information. Something about the same way we each dealt with the question “where are you from?” alerted me to listen more carefully. As my neighbor listed the countries she had lived in as a child, “Burma” rang all the bells. “Alice! Alice Cannon! Are you Alice Purnell who lived next door to me in Rangoon?” She is. Our families were next door neighbors when Alice’s and my fathers worked for the American Embassy in Rangoon, Burma, in the early ‘50’s. We were very small then, but we could remember our cats who were siblings, our shared disaster with the bees in the hedge, and our study partnership in Miss Gevney’s one-room American school. Alice is an only child, but she remembered my little brother, too.

Over and over, we asked each other how it came to be that over 50 years later we found each other and discovered a shared interest in the legacies of slavery and the descendants of the enslaved communities linked to our own lives. Since that reunion, we have spent days together, and we are capable of talking about linked legacies way into the night.

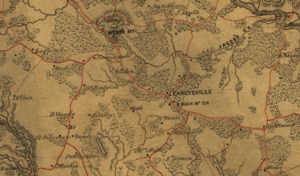

Old map of the Earlysville, VA, area

One of the most compelling stories I learned from Alice and her husband, Jon, was about what happened when they moved to Virginia and bought an old house in Earlysville. Alice wanted to know more about its past; she had no thought about the enslaved people who lived there. She hadn’t grown up with a family legacy of slave-owning in any case.

Bleak House, front entrance

But she wanted to find out about the place. What she learned was that Dr. James B. Rogers bought Bleak House plantation from the heirs of William Michie in 1836. The house in which Alice and Jon live today was built in 1854 and occupied by James and Margaret Rogers by 1857. James and Margaret Rogers’ descendants were defeated by the Civil War, and moved to Kentucky. Alice has contacted them and let them know they have kin among the descendants of their ancestors’ enslaved people, but they so far have no interest in the information or in making connections.

Typescript, Rogers’ list of enslaved people

A neighboring farmer, Mr. Garrison, told Alice that the previous owner of Bleak House had researched the property, including the enslaved people, up to 1863. Garrison gave Alice a little book listing the names of the enslaved people of Bleak House. It took her breath away. Like a flash of lightning, the whole story of enslavement and injustice descended on Alice, and she decided as the current owner of Bleak House and a steward of its land, she must make a commitment to find and connect with the families and descendants of the people listed on that paper.

Bleak House, possible detached kitchen building

Through years of work, Alice has put together diagrams of the enslaved families’ connections, has located descendants in Virginia, Washington, DC, West Virginia and Ohio, and has accumulated photos of family members past and present. Two family reunions have been held at Bleak House, and Alice has shown the families to the ancestral graveyard for one of their lines. Books of family information and reunion photos have been created, and Alice has been working with the Central Virginia Historical Researchers and has put the story and the family information from Bleak House on their African American Families Database

Page of census records

Alice has also become a font of information about local area enslaved families and helps people researching their connections to those families make progress in their quest. Her work includes a guide to researching African American family lines from slavery to freedom, using a real example and images of the relevant documents, as well as a description of the questions to ask oneself in making connections from an inventory to a census record to the Personal Property Tax List. Another member of the Researchers organization, Lynn Rainville, has assembled African American Research Resources (Albemarle County)

What Alice Cannon found out about the enslaved community of Bleak House Plantation, and how its descendants have reconnected to the property will be described in Parts 2 and 3, to be published November 22 and December 8.

Alice and Jon Cannon represent the best of us. I am so grateful to them for what they have done to illuminate our past.

Thank you so much for this heartening story, Prinny! Alice has done what I hope to do, and it’s quite a task. Kudos to her, and to you for telling the tale.

What a delightful story, Prinny! It’s amazing enough that you and Alice, following each of your distinctive paths, found yourselves sitting next to each other 50 years later at a gathering of people committed to unearthing the history of slaveholding and the lives of the enslaved. I would like to be the proverbial fly on the wall to listen to conversations. And THEN to read of the work that Alice Cannon has been doing — wow!. This is such a confirmation of being linked through the places we’ve been and where we find ourselves. More please!!

This is a fascinating connection. Bravo to Alice for taking this journey and adding so much to our understanding about slavery and how to find descendants through hard work and diligence. Thank you Prinny for this story. Awaiting the next installments.

A thread of altruism runs through genealogy and family history research. I hope folks have discovered ‘genealogy angels’ who’ll go out of their way to look up remote records, take photographs and the like. My work benefits from genealogy society chapter researchers and mere family history investigators, who have preserved records and are prepared to assist at no cost.

I will simply compare freewill offerings to a ‘scroll’ of family history I’ve inherited from a Great Aunt (once a national President of Daughters of Colonial Wars). It is illustrious; she paid a top-notch genealogist from D.C. for it. (Contentions were also later to be found flawed, the august Colonial Dames of America will not accept some of the assertions.) My aunt’s intention was to be elevated in esteem, so much so that her sisters … with a conjoint heritage … experienced emotional distance.

I hope Cannon’s extraordinary efforts, to link others to their pasts … despite the social quagmire that relationships forged in acknowledgment of slavery tend to be … are indications of a new era. Our ancestors’ common experiences, freely shared, form some of the tenets I found when Coming to the Table. I realize it’s not an easy task; not in the social milieu, and not in the difficult work of unearthing and culling through records not as well preserved as those which elevated personal and ancestral status.

A generational divide remains. A distant cousin holds a bible containing slave records for another branch of his family. He’s ninety-eight years old, and reluctant to allow me to have it scanned. I’ve wondered about the 19th-century recorders of those birth and death entries: “Did they feel kinship? Pride of ownership?” My contact expresses trepidation about revealing his peoples’ slave-owning past. I sense my attitudes are more like Cannon’s: family history research gives me satisfaction; empathy alone has me thinking others would feel gratified in learning the documentary record. I add to my sentiments another layer. My high-status kin (Great Aunt Corday socialized with Bess Truman while President of DCW) sat on wealth derived from slave labor her forebears coerced; it seems just that we now tease that out.

BitterSweet seems to be a place where our angelic capacity can embrace the lower order of of perpetuating cultural dominance arising from unacknowledged harm.

Such an amazing story!

Sent from my iPad

>