Part 2 – Finding the Descendants of the Bleak House Community

Part 1 narrated what happened when Alice and Jon Cannon bought Bleak House, the remnant of Bleak House Plantation, and then found a book with the names of its enslaved residents.

Alice was galvanized into learning about those people and finding their descendants. Part 2 tells what she learned about them.

James B. Rogers handwritten family tree

The stories of the many people Alice’s research uncovered and connected into family groups are stories of cleverness, intelligence and education, hard work, perseverance and success, love and self-determination.

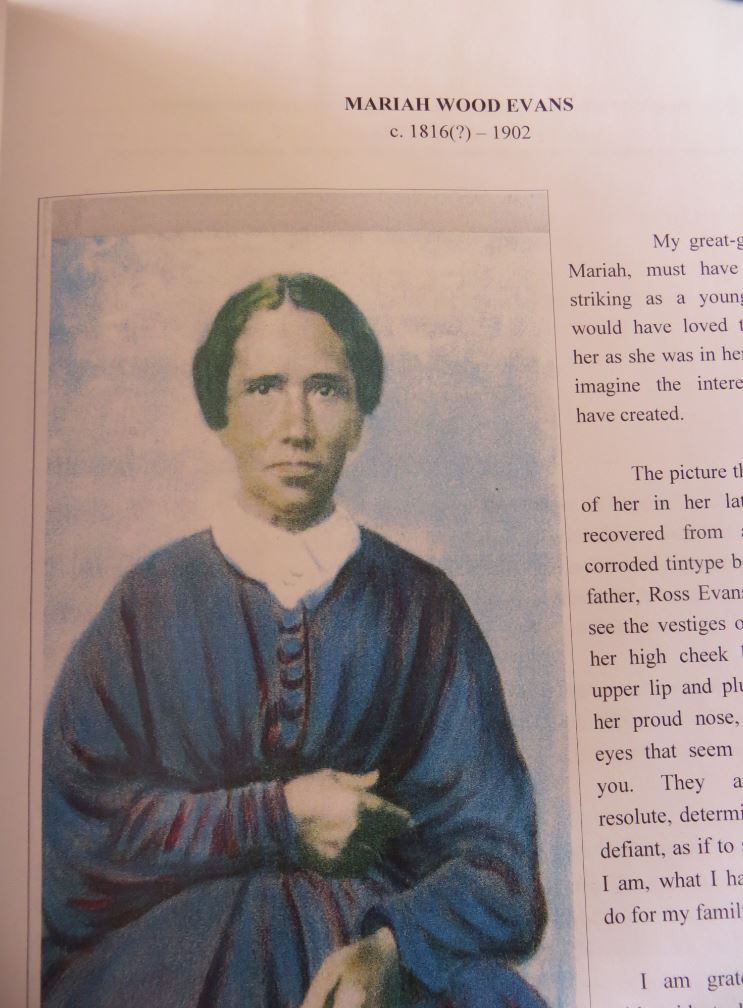

Photo, Mariah Wood Evans

The best documented Bleak House family was the Wood-Evans group. Bleak House’s owner, James Rogers’ wife Margaret was from the Wood family; two of the Rogers’ enslaved women were mother and daughter, named Hannah Wood and her daughter, Mariah Wood.Oral history states that Mariah’s children, Fanny, Mary, Thornton, Nathaniel (Link), Calvin and William Bernard, were fathered by her owner, James B. Rogers. ; their names were William Bernard and Nathaniel, known as Link. The first two children Mariah had, Robert and Angelina, were perhaps fathered by Perkins Evans, a blacksmith owned by the Michie family on an adjoining plantation, Longwood. After Emancipation, Mariah and her children lived with Perkins, and as families might do, Perkins took Link on as his apprentice.

Perkins Evans was enslaved by the Michie family, possibly fostered by the the housekeeper at Longwood, Cloe Evans. She was a free woman of color who was not directly related to him. She bought land and lived in her own house until she sold it to the Michies in exchange for a life tenancy.

Cloe’s daughter, Harriet, was a business woman, and when she died in 1870, she left everything she owned only to the women in her family and community: to Mariah and Fanny Evans, to daughters of “Beau Jim” Michie of Longwood, and to the daughters of her white friend Elizabeth Barksdale Terrell. Harriet’s estate included jewelry, fine clothing, furniture and bonds.

Link Evans’ house, Earlysville, VA

Mariah Wood Evans’ oldest son, Link (Nathaniel) learned a trade from his step-father, Perkins Evans, and continued working as a blacksmith his whole life, in Earlysville. He was also a landowner, and as such was “invited” to vote by the white town officials. His children were Sarah Belle Evans, Roscoe Conkling Evans and William Evans.

Mariah Wood Evans’ son Calvin moved away from home at age 17 and went to West Virginia. He returned home to marry Ada Cave Tyler and took her back to WV. He wrote a memoir of his life as a slave, describing how one of his jobs as a child was to fan the family while they ate.

Opening page, compiled history of Hannah Wood

His grandmother, Hannah Wood, was the cook; his mother, Maria Wood (Evans), was the housekeeper; and Calvin did chores. At one point, the owners intended to give Calvin away to one of Rogers’ brothers, but Calvin cried so pitifully all the way to the train station that his new owner felt compelled to release him to run back home. Calvin had a son, Ross, who remained in WV, but his grandson, Jim Evans, lived in Ohio.

Thornton Evans became a businessman in the Earlysville area. He married Marinda, owned by another branch of the Michie family. In her later years, Mariah Wood Evans lived with Thornton and Marinda until she died.

One of Mariah Wood Evans’ daughters, Mary Evans Ray, married and then divorced after being abandoned by her husband. There is so far no information about the life of another daughter, Fanny Evans.

Like his brother Calvin, William Bernard (Wood) Evans moved to WV and attended Storer College. He married another Storer graduate, Marica Lovett, and became principal of a school for African Americans in Harpers Ferry.

The Wood-Evans family has a strong oral history tradition. Members gather each year in Talcott, WV, on the banks of the Green Brier River, at a family camp. They visit and share stories. Eventually, many of their stories were written down.

The Wood-Evans family has a strong oral history tradition. Members gather each year in Talcott, WV, on the banks of the Green Brier River, at a family camp. They visit and share stories. Eventually, many of their stories were written down.

Another family associated with Bleak House is the Woodfolk family, and so far much less documentation about them has emerged. Armistead Woodfolk did the carpentry and made the bricks for Bleak House. Post-emancipation, John Woodfolk lived in Washington, DC, and had a government job. Nelson Woodfolk moved to Buxton, OH, and worked as a coal miner.

Genealogical information associated with this story can be found with through the Albemarle County Historical Society, in the Central Virginia Genealogical Association, and in the African American Families Database.

Part 3 tells the story of finding the descendants of the Woods, Evans and Woodfolks and their return to Earlysville and Bleak House. It will appear on December 8, 2015.

Can I request a correction of the mention of the memoirs by Calvin? I don’t believe those exist. The memoirs you refer to are most likely those that my family members recorded of my great-grandfather, Ross, Calvin’s son, on audio tape and then transcribed to text. I know it’s a small detail, but I feel invested in seeing any documentation of my family history reported as accurately as possible.

Kathryn – Your comment will stand for the correction. If there’s anything more that should be added, please do make another comment. I agree that the documentation needs to be as accurate as possible, but we’re not in a position to correct the original post. Alternatively, if you would like to “guest post,” and write about the research and documentation of your you family’s history, we’d be very happy to publish it here. Prinny Anderson, interviewer

Hi, I’m an Evans descendant, and I’m wondering about the book written by Calvin. Do you have more information about this? I am aware of some memoirs recorded by Ross, my great-grandfather (Calvin’s son) where he relates the stories you mentioned, but I have heard nothing about a book by Calvin. If you have some more information about this, I’d love to know about it!

As impressed as I was by Part One of this story, I’m even more excited by Part Two. There is a wonderful connection to my own post, “Redrawing A Community – A Washington Descendant’s Journey, Part Two.” The grand children of Solomon Thompson, who was enslaved by my family, and whom I wrote about in my post, attended the same school where William Evans taught – Storer College in Harper’s Ferry. This school (closed in 1964) played a substantial role in African-American education; how great that it plays a part in two separate family histories on the Bittersweet blog.

A note on Ann Neel’s question about John Brown’s effect on the local community – Jefferson County, West Virginia. I interviewed Jim Talbot, of the Jefferson County Black History Preservation Society, who told me that “right after WW1 that the black veterans got together and formed and American Legion named after Sheilds Green and John Copeland. And I thought that was pretty brave.They were two of the people that fought with John Brown.”

As the Bleak House people come into focus, this intriguing story raises many questions even on first read. For one instance, is Calvin Evans book available? For another, I wonder how unique it was that an enslaved child could free himself by sobbing, because the sobbing must have happened at slave sales all the time! And how did John Brown’s rebellion affect the community of Harper’s Ferry (is it the same one?) and the Wood-Evans family members? Also, is it not sort of amazing that one Maria Wood’s sons with her master Rogers was called “Link”? Good work, Prinny and Alice!

The story as told by Ross Evans (Calvin’s son) says that the station master told Rogers’ brother’s wife that they would never get Calvin through Washington if he “was making noise like that”. This was about a year before emancipation, and the family was transporting a slave to a free state (the end destination was Philadelphia, where Rogers’ brother lived). So, I’ve always assumed they sent him home because his crying would have brought attention to their illegal activity.