A blessing of tracing genealogy back to colonial America is that so much of its documentary history has been so richly excerpted in published histories or reproduced in full in a variety of formats that it’s not always necessary to seek out the original sources. And of course, the internet has opened the doors to these documentary resources even wider.

That said, I had never seen a complete set of any of my New England ancestors’ wills or inventories of their goods and chattels. Either a book transcribed parts relevant to the writers’ purpose or somebody couldn’t find the other three pages they’d copied at the archives, or… you see what I mean.

Completeness of documentation has mattered to me not just on principle but because I have a special interest in information typically saved for the end of a given inventory, whether in the New England of the 1750s or the South of the 1850s—the presence of slaves. A combination of focus only on the household goods or real property, and a not infrequent desire to downplay the role of slavery in colonial New England, can leave the existence of listed slaves on that last page unknown and even ignored. So to me, the last page matters most of all.

You do the same thing once, twice, three times, and it begins to seem second nature; the impact of the experience is lessened as its details are memorized through repetition. But this familiarity has never cushioned for me the impact of seeing an enslaved person’s name, description of skin color, age and gender, and the monetary values assigned. Such was my experience all over again earlier this month when I took advantage of Ancestry.com’s offer of four hundred years worth of American wills and estate inventories. At last, I thought, I would get to see inside some of those old gabled houses, long vanished, around which mists and red leaves and innumerable dramas of people black and white had swirled in little towns of southeastern Connecticut.

I had already read most of the will of my eighth great-grandfather Benajah Bushnell, at whose death in 1762 the upright old man left hundreds of acres around Norwich in New London County, a costly but sober wardrobe, and several pious books. Benajah had already sold a few years earlier a slave named Guy Drock, whose purchaser, Sarah Powers, was a white woman who paid in cash and two years’ indentured servitude in the Bushnell household to live with the man she loved. (My account of meeting Guy’s and Sarah’s descendants in Norwich in 2012 is given in this article.) I’d not seen the will and inventory of Benajah’s wife, Zerviah Leffingwell Bushnell, who died in Norwich in 1770, and I was especially interested in it because I hoped it would shed light on a mystery, namely how the two story yellow house in Norwich called the dwelling of Guy Drock came to be owned by him—whether deeded to him by Zerviah or transferred in some other way, or whether it had been Zerviah’s home while alive and Guy’s and Sarah’s upon her decease.

Gravestone of Zerviah Leffingwell Bushnell (1686-1770), daughter of Ensign Thomas Leffingwell and wife of Benajah Bushnell of Norwich.

The documents didn’t help me as much as I’d hoped, though they did reveal my eighth great-grandmother to have been a rather interesting lady, with her fashionable wardrobe, her silver eyeglasses suspended from a chain of amber beads, and her ownership of a book titled Aristotle’s Masterpiece, or The Secrets of Generation, a 1684 sex manual said to have been banned in Britain as recently as the 1960s. A salient image in this book is to be found in the frontispiece illustration, showing a naked female figure covered in hair and a black baby running after her, woman and baby rendered thus by the parents’ “imagination”—in other words, bad thoughts causing “bad” results, like that worst of all possible chimeras for a white couple, a black-complexioned child.

I had to go back a generation, to Zerviah’s wealthy father, Ensign Thomas Leffingwell, whose large estate was inventoried after his death in 1724, to find the enslaved people I was looking for.

I deciphered the descriptions of velvet cloaks and calamanco gowns, chamois gloves and many a “wigge”, silver buckles for shirts and shoes, riding hoods and pillion saddles (male and female), walking sticks with silver heads and ivory heads and a carved horn handle doubling as a whistle for hunts. Part of me enjoys rummaging among these undoubtedly beautiful things. But part of me cannot help but stand back and soberly acknowledge the African faces looking out at me from my ancestors’ lovely rooms, puzzled by my twenty-first century interest in their fate, or angered by their chains, or solemnly enduring what they had come to accept as inescapable. How easy to forget that alongside these trappings of material prosperity were human beings who, unlike silver porringers and gauze fans, were left at the back of the inventory bus but still counted as components of what made up a family’s sum total of wealth and standing in a community.

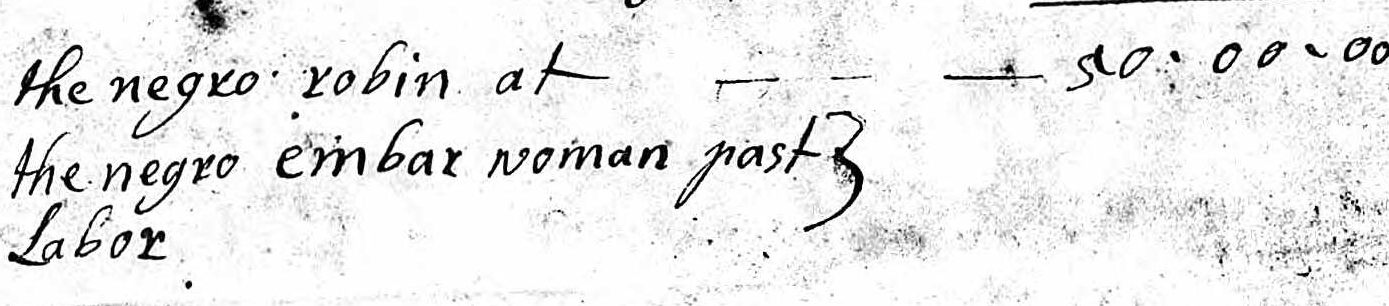

And there they were. Embar or Amparo (Spanish for “protection”) was an elderly “woman negro” in Thomas Leffingwell’s household, her name suggesting Atlantic creole origins. With her is Robin, an African male, and beside them is what for 1724 is the low valuation of £50. Embar is described as “past the age of labor”—too old to work and, thus, of little to no value. Robin, though, if a hearty young man in his twenties or thirties, should have been priced far higher. If he were elderly, he would have been described as such. My guess is that Robin was more boy than man, supported by the fact that he appears years later in the household of Ensign Leffingwell’s son-in-law, Benajah Bushnell, husband of Leffingwell’s daughter Zerviah.

I have been to the Leffingwell House, now a museum, its rooms full of gorgeous colonial paneling, age-blackened ceiling beams, wide plank floors that crack like buckshot when walked on, its glass cases containing the sheen of displays of old family silver, flintlock guns, Thomas Leffingwell’s silver-topped walking stick. (Had Robin or Embar ever carried it for him?) I had even been in the basement, where I saw the so-called “north door”, where according to tradition slaves were auctioned by the Leffingwells in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Silver-tipped cane of Thomas Leffingwell (d. 1714), father of Ensign Thomas Leffingwell, on display in the Leffingwell House.

I didn’t see it on my tour, but the 1724 inventory says there was a “kitchin chamber” (a room near the kitchen) containing a bed and, tucked under it, a trundle bed. I don’t write fiction, but a combination of imagination and logic suggests a scenario for this sparse little room—that Embar, the elder servant who may have nursed generations of Leffingwells and, though deemed without monetary value, was respected and possibly loved by her white owners, was given the comfortable bed. And Robin, busy boy about the house, slept in the trundle bed in the room with Embar or, more likely, in a hall somewhere outside it. Somehow this image softened the hard edges of why Embar and Robin were living in the Leffingwell house in the first place. How easy it is to be lulled by pretty clothes and silver spectacles into value judgements about what the people who wore them were like—just as easy as contemplating that “kitchin chamber”, the elderly creole woman and the young boy, the stories she may have told him of the Spice Islands and masters cruel and kind and the sharp sweet tang of sugar cane, so strange to imagine on these cold and remote New England shores.

All the best fairy tales close with a sting, and such is the case with Embar and Robin. For all they were human beings, they sit at the bottom of a list on the last page of Thomas Leffingwell’s inventory, one which begins with clothes, furniture and land, and ends with livestock. And on that final page, over the column starting with cattle, sheep, pigs and horses and finishing with the names of two human beings, is a comprehensive heading which clearly defines what they were to Thomas Leffingwell and enslavers like him: “Creatures”.

There are doors which, once forced, cannot be closed again. And they should not be, not just in the name of the truth of New England’s too often overlooked legacy of slavery, but for the sake of the Embars and the Robins who, free of charge and left to the bottom of the list, nonetheless helped build and support a prosperity and a culture which neither benefited nor respected them.

Hi Grant,

My son and I have speculated that your ancestor, Thomas Leffingwell may have left a very young slave boy to his cousin, Benajah Bushnell in his will. Not having been able to locate Leffingwell’s will, we are left with only speculation as to whether this was Bushnell’s source for Guy Drock. Can you supply any information about that possibility.

I hope all is well with you both.

Don Roddy

Hello Don, we have forwarded your message to Grant.

Calling out the names of the enslaved is one way to set free people from the pages of historical documents where they are described, in this case” as “Creatures.” Thank you Grant for this beautifully written liberation from the list of oppression.

Thank you Grant and Prinny! “The lifting up and calling out of names” — yes! I appreciated the way you guided me/the reader through the welter of detail in the inventory. Call out the names —

We’re doing this at Love Cemetery in East Texas. Calling out the names.

We’re going back in to clean, the 1st time we’ve been able to get into the cemetery in a year, the last time we can go in this year. We cannot go back in until Feb. 1st, 2016. Yes it’s about keeping the land cleared so se can care for the graves that are there but also to discover unmarked graves, hidden markers, we are still finding the names.

“Memory or oppression,” Kundera’s biting summary of our choice.

I welcome any way in which other members of CTTT might join us thank you, China

The crisp, rich detail of this account make Embar and Robin all the more real for me, give me space to imagine their faces and appearance. But reflection on their listing on the last page, under the heading “Creatures” somberly reminds me why today we must, we absolutely, loudly and repeatedly must cry out “black lives matter.” Because in these old documents, from 200 and 300 years ago, we see how readily the dominant white culture, the leading citizens of their time and place, did not give any importance to black lives at all. After two or three or four centuries of putting black lives at the bottom of the page and the end of the list, it is imperative that we lift them up, call out their names, and make sure they matter, and that we do so over and over again until the fact starts to sink in and shows up in our political and social behavior. Thank you, Grant, for contributing to the lifting up and the calling out of names, of putting them at the top of the list.

The names are sacred, the bearers beloved. Thank you, Prinny, for helping me speak their names.