We are continuing our series, and will be sharing artwork and writeups of the creative process, from our Linked Descendants’ working group members.

Some of us have begun to explore our thoughts, feelings and the multi-layered experience of finding our ancestors, through collage work. We created collages on our own using a specific framework as a starting point (eg: a river of life, an explosion of awareness, a tree of knowledge or life, a path towards or away, etc.) and then shared with each other in small breakout groups. Most of us found this to be a powerful way to further process our often conflicting emotions. Expressing what we know in visual, rather than written terms, allows for increased awareness, deeper insight, and further integration of the new and/or more difficult truths around our ancestors and overall family histories.

Today’s collages and process descriptions have been generously shared by Antoinette Broussard and Jerrie. (Click on each image to see it in more detail)

DISCOVERING REBECCA

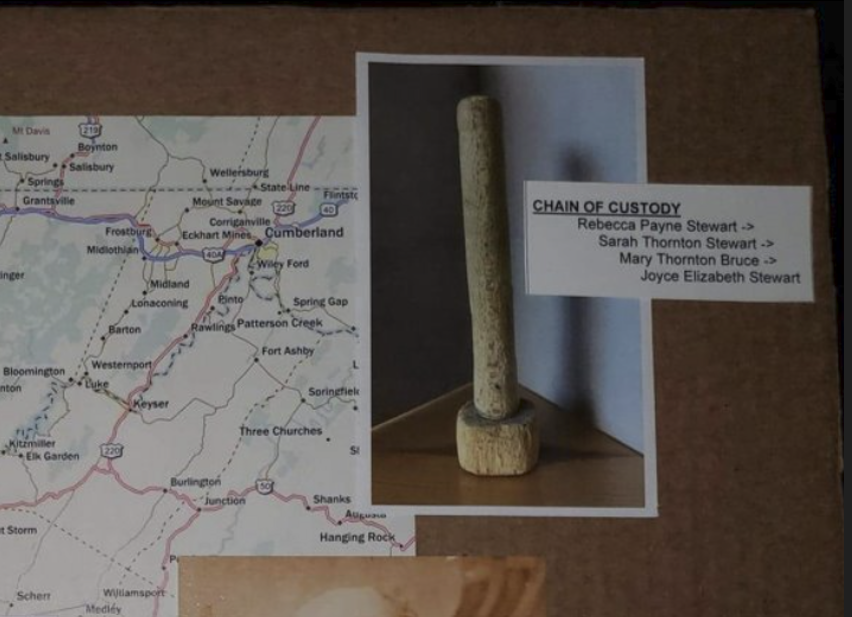

My collage is about my search for Rebecca Payne, one of my great-grandmothers.

What we know about her is so limited. She was born around 1829 in Hardy County Virginia. She was probably enslaved half of her life. She was emancipated in 1863 and married Fortune Stewart. She had sixteen children who survived to adulthood. After her husband’s death in 1888, she lived with two of her youngest children until her demise in 1910.

ANTOINETTE’S COLLAGE

Berry Benjamin Craig (on the left) was my maternal grandfather. He was born enslaved in December 1863, in Platte County, Missouri a year after the Emancipation Proclamation had passed. Missouri did not secede from the union and that allowed them with a strong Confederate presence to keep their slaves, enslaved. Eighteen years ago, I inherited my grandfather’s meticulously written and typed manuscripts on onion-skin paper. I’d not known him to be a writer. When I look at his photo I remember my mother explaining her father was a self-taught man. She’d repeat the term “A mind is a terrible thing to waste” which always reminded her of the education and opportunities he missed out on because of his race. My mother told me he studied and wrote at night when he returned home from work. His manuscripts were completed in the early 1930s. They were about his enslaved family including his biological father, William Paine Wallingford, the enslaver.

On the far right, is a photo of Wallingford, my great-grandfather. I’ll refer to him as W.P. What a mean, terrible man, I always think. I cringe when I imagine what he must have done to Violet. He was the perpetrator, who never paid for his crimes of enslavement, rape, and unlimited abuse of my great-grandmother Violet Craig Turner (at the top of the page), and his abandonment of the seven to eight children he fathered with her. She was enslaved by W.P for at least 15 years, worked on his farms, and birthed and nurtured her children. W.P. never assumed responsibility for them. He also had 11 white children with their white mothers.

I started researching my grandfather’s stories to see if they were fiction or non-fiction, to see if my grandfather had put his literary foot to a true story. I needed to validate his work in order to include it with my research. I wanted to get his stories published.

Violet, her five brothers, and parents were born in Kentucky, as was W.P.

I traced them from enslavement in Missouri back to Kentucky.

I reviewed W.P’s land records, court records, biographies, family histories, and census, looking for clues. I needed to know the history of Violet’s family.

I reviewed the 1833 will of W.P’s father, John Wallingford, filed in Mason County, Kentucky. There were two unnamed children in the will; one was Violet’s age, born in 1828. Violet had named five of her children using the same names listed in John Wallingford’s will. I studied the records of Wallingford family members who had inherited John Wallingford’s slaves. Maybe they were my family members. That’s how the enslaved remembered their families. They pass down the names.

I studied the families that accompanied W.P. from Kentucky to Missouri to see if there were any transactions between them with clues to Violet’s family.

These enslavers along with the Wallingford’s had glowing reputations written into their histories—“who traveled down the Mississippi, Missouri, and/or Ohio Rivers, to conquer the wilderness and cut out a homestead, build a community, in Kentucky and Missouri. They valiantly fought the savage Native Americans, and how brave these pioneers were.” That’s what I found written in the family histories, located in the libraries and historical societies.

They were sheriffs, judges, ministers, doctors, newspaper editors, and farmers that used our black families, taking them apart as human beings. Black people were bred, used, chewed up, and spit out. Abandoned. And these perpetrators got away with it.

We were made invisible. They buried the truth. Before 1870 our history is mostly non-existent. Every time I look at W.P.’s photo, I almost immediately look away, because I am reminded of his and his comrade’s injustices.

Very little is known about Violet. She is listed in the 1850 slave schedules only by age and color, with a 9-year old black child, both owned by W. P. Maybe the child was Violet’s child? But there is no clarity of parentage.

In the 1860 slave schedules, the 9-year old child is gone…maybe sold, died, or rented out, because by that time if she were still alive she’d be 19. I’ve never figured out who she was. There would be seven children by the time Violet was freed by a Missouri ordinance or the 13th Amendment in 1865. My great grandmother Violet left pregnant, with five children, one ten-year old child was sold by W.P. to fund his involvement with the local confederate militia, and one not accounted for.

W.P. lived with his white family, in an upper class neighborhood in St. Joseph, Missouri. He lived 20 miles from Violet and her children across the Missouri River, in Leavenworth, Kansas. According to my grandfather they lived in a shanty. When Violet’s children were older they crossed the river to ask W.P. for money.

“We need help…you’re our father,” they said to W.P.

“How do you know I’m your father? W.P. said.

“We know, because Mother told us,” they said.

But he did not give them money, or land. He left it all to his white children and wife when he died in 1875.

W.P. can go back to England on his family line. My family lines were intentionally erased to erase our existence and their owner’s sins, and to promote the lies of their so-called goodness. I resent it that my nose always gets rubbed into the unfairness of it. I have to research his family in hopes of getting answers about mine.

Nettie Craig Asberry (at the bottom of the page) was the 8th child Violet was pregnant with in 1865, when she and her children were freed. Nettie was the only one of the 8 born free. Her older siblings pooled their money to help with her education. In 1883 she graduated with a Teacher of Music Degree from the Kansas Conservatory of Music. For many years, Nettie was a choir director for the (A.M.E.) African Methodist Episcopal Church. She taught music in the schools in Nicodemus, Kansas. Later she moved to Seattle and then Tacoma, Washington where she helped establish African American women’s clubs for their self-improvement and independence. Nettie co-founded the Tacoma chapter of the NAACP, and she fought for women’s suffrage and people’s civil rights. She died in 1968. Her former home was purchased in 2021 by the state of Washington and is being renovated into a community center to honor her work. She promoted harmony among the races and wanted everyone to enjoy a good life. When I look at her photo I think Bingo. My family’s hard work to survive the terrible ills of slavery lives in the accomplishments of Violet’s children.

— Antoinette Broussard www.antoinettebroussard.com

Even though I grew up about 15 miles from where Rebecca was enslaved and I have family still in the area it have been difficult to determine which of several plantations/farms held her. Without irritating or embarrassing the descendants of potential enslavers I have tried to use documentation (deeds/wills) and references to find out who held her and who her parents were. Working with courthouse documents is difficult from a remote location during a pandemic. But because descendants of the enslavers are clients of my sister I don’t want to risk her business opportunities. I have some clues on her lineage with the help of DNA matches.

Dear Karen: You are right! We are blessed. We’ve found and have each other on this journey, the descendants of the enslaver, the enslaved, or both. I feel a genuine comfort traveling together with all who are concerned! Thank you! Toni

Dear Julie M. Finch: Your comments are inspiring. It keeps me moving forward and committed to telling their history.

You remarked about this statement: “Violet had named five of her children using the same names listed in John Wallingford’s will. I studied the records of Wallingford family members who had inherited John Wallingford’s slaves. Maybe they were my family members. That’s how the enslaved remembered their families. They pass down the names.” I intended to convey that Violet had named her children with the same names as several slaves in W.P.’s father’s 1833 will. They were on his inventory list. Violet did not name them after the enslaver Wallingford, but used the same names of the enslaved. That’s how slaves passed down names and remembered their ancestors.

I think maybe these enslaved were my relatives. There were five names used. Violet named her children three of these names and two more names appeared in my grandfather’s manuscript.

Thank you, Ms. Finch! I appreciate you! Antoinette

Jerrie, thank you for this beautiful work, the art and the words bring Rebecca to life in our hearts, the potato masher a relic both precious and painful…to crack the code..that is our quest..I’d love to know your questions and if they are anything like my own.

Toni…your art and words like Jerrie’s bring your people to life and make me long to lift them out of that misery created by people much like my own, the W.P.s of this land who never paid a price and passed their sin to the generations. We are so blessed, we who have found a way beyond that bondage of body, mind and spirit and fashion ways to overcome.

This is so beautiful, and beautifully written. Thank you so much Antoinette. And also thank you for the information that the families of the enslaved always named their children, from rape or other kind of relationship, after the enslaver. That’s how they kept track of the families.

I also liked the photos of everyone; they added so much.

Amazing that your great grandfather wrote a manuscript. Maybe we could see a

page of that some day.

And I loved reading about your ancestor Nettie, what an accomplished woman.!

And I loved how you wrote about W.P. keep that in.

Thanks so much,