This is the final post in our series that started in 2021, where we share artwork and writeups of the creative process, from our Linked Descendants’ working group members.

Some of us have begun to explore our thoughts, feelings and the multi-layered experience of finding our ancestors, through collage work. We created collages on our own using a specific framework as a starting point (eg: a river of life, an explosion of awareness, a tree of knowledge or life, a path towards or away, etc.) and then shared with each other in small breakout groups. Most of us found this to be a powerful way to further process our often conflicting emotions. Expressing what we know in visual, rather than written terms, allows for increased awareness, deeper insight, and further integration of the new and/or more difficult truths around our ancestors and overall family histories.

Today’s collages and process descriptions have been generously shared by Judy Davidson, Brian Crane, Cindy Carroll, Libby Floch and Pam Burris (AKA Palmer Ownschild).

*CONTENT CAUTION: Mention of violent acts

FAMILY TREE: A MEDITATION ON SILENCE, TRAUMA, GRIEF AND HOPE

My collage shows a large tree in leaf illuminated by soft golden light. Smiling faces peer out from among the branches, photographs of beloved parents and grandparents. But among those branches lurk disturbing images: shackles and guns, and a skull lying among the roots. There are a lot of complicated and conflicted feelings that went into this piece, and I wrestled with how to portray them.

I started learning about my ancestry when my father received a copy of an old published genealogy from my grandmother. It had hundreds of pages of who begat whom interspersed with brief hagiographies of prominent men. I shared my father’s fascination with the history, but in pre-internet days and living far from the places our ancestors lived, the book was all we had, along with fragmentary memories passed on by an older generation more interested in looking ahead than behind. It was a spare tree, scant on details and full of silence.

When I was a student, I had access to a research library and began to fill in some details. But it wasn’t until years later when the quantity of internet accessible documents grew, and the number of people conducting online genealogy seemingly exploded, that I was able to really fill the voids and flesh out the stories of people’s lives. I found out about the 17th-century Swedish ancestors no one in my family knew about, multiple Revolutionary War veterans, a 19th-century apothecary, and an 1860s frontier doctor who opened a clinic for the poor in Idaho City. Most of what I found was ordinary and uncomplicated, but slowly more difficult and painful stories began to emerge.

I doubt my parents or grandparents had any idea that any of our ancestors had held others as property. Our family history played out mostly in the north, so like many white northerners we assumed that slavery was a scourge that afflicted other regions and other families. Instead I found that several held others in slavery (at least 6 that I know of as of now) including a 5th great grandfather who had been transported to America as a convict but who held 19 people in slavery when he died in 1789. I found that my ancestor who was his grandson repudiated slavery, leaving Virginia in 1818 for Ohio, possibly taking some of the family’s enslaved people with him in order to give them freedom and land. I found other ancestors who participated in horrific massacres of indigenous people, while another on at least one occasion acted as an intermediary between the Lenape and the colonial government of Pennsylvania. My family tree entangles slave owners and Quakers, people of violence and Mennonites.

I struggled with how to represent a tree that has born such mixed fruit. How could I be honest about all of the painful chapters without feeling like I was betraying my parents and grandparents along with all those whose lives seemed so different from those who participated directly in slavery or massacres? Of course even the ancestors of whom I am proud lived on land taken from Native people, and their livelihoods benefited from the profits of unpaid labor.

Rather than attempt an easy resolution of all these contradictions, I chose to incorporate images that evoked for me both the best and worst of my family’s past. The faces of my parents and grandparents are there along with objects associated with some of my family heroes. There too is a part of a will that named people as slaves and shackles hanging among the leaves. Suspended rifles and a skull half hidden at the base memorialize the violence my forbears inflicted. The nostalgic glow contrasts with these painful tokens and reminds me of how my family’s history was first passed on to me, and how I naively received it. It is meant to be simultaneously beautiful and ugly.

But my intent with the light isn’t entirely bitter irony. Rather late in the process, I added a piece of artwork embroidered by my mother for our church: an image of the Holy Spirit as a dove, descending in a flame of inspiration. I still don’t know what to do with all of this, or what it says to me about who I am. But I am hopeful, both of this moment and my journey in it.

— Brian Crane

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS HARRIS COUNTY, GEORGIA?

Getting my DNA done through Ancestry.com, led to a chance encounter with a long-lost relative, and knowledge of my family’s involvement as enslavers in pre-civil war Georgia. This collage represents the path I have followed since learning those facts as I tried to better understand the nature and extent of my relatives’ slave owning past. As I dug deeper, I learned that my relatives were not only engaged in slavery, but they were also active beneficiaries of the Indian Land Removal actions in that area.

My inquiry has led to an ongoing generation of questions about the historical facts and my personal links to them. I have looked at maps and read wills and narratives about the period. I also searched for visual artifacts that would help me to envision the issues—from photos of the plantation home itself, reprints of Confederate money, handwritten documents, as well as images of the cotton that was at the heart of the slavery, and the birds that pecked in those same fields. Recently a cache of childhood photos emerged and I have included one of my grandfather who links me with those enslavers (and knew them personally).

Doing the collage and reviewing my work in a visualization helped me to see several new things about my inquiry:

- The enslavers are all named — first and last name, with more information in genealogies that are available. However, the enslaved only exist as a first name, age, and price in the addendum of a will in 1862.

- In addition to the enslaved labor, the Indian land, available at almost no cost through the land lotteries in which my relatives participated, were what made John W. Davidson, my 3rd great grandfather, a very wealthy man.

- William Davidson, my 2nd great grandfather seems to have had a particularly strong connection to the world of the plantation. After the Civil War, he re-bought the plantation home the family had lost, and then lost it again himself before leaving for East Texas with his older sons (including my 2st great grandfather, his son John). William’s son John eventually traveled all the way to Oregon, losing much of his connection with relatives in Texas. My question now is: how had this John been influenced by his father William’s deep ties to the idea of the plantation and the lost cause of the south, and how did this affect his son, my grandfather Richard…and, eventually, me?

— Judy Davidson

THE BALDWIN BOYS: BURR PORTER, MAURICE HENRY, SAMUEL MILLS, REVEREND BURR, GABRIEL, JARED

Burr Porter was my grandfather. He died in the 1918 flu when my mother was two. His father, Maurice, was born in 1861 (Knox, Missouri) to Clarissa Millard and Samuel Mills Baldwin. Two years later Samuel moved to WDC, leaving Clarissa and Maurice in the care of Solomon Nelson Millard; Clarissa died several years later.

My intrigue has been with Samuel Mills, son of Reverend Burr Baldwin, who had many church postings in Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Reading between the lines and because he started one of the first Sunday schools in the country (Newark, NJ) offered to African Americans, I wonder if his values ‘for all’ imposed difficulties with his parishioners.

How did Samuel get from Pennsylvania to the tiny spot of Knox, Missouri? In a continued quest, one day I went ‘sideways’ in a simple Google search. I typed in Clarissa Millard’s name along with that of her sister Lucy Millard.

What a reward! Around 1857, Lucy fell in love with Isaac Berry, who was enslaved on a farm adjoining Solomon Nelson Millard’s. With the help of Mr. Berry’s enslaver, who was also his half-sister, Isaac made his way to Canada as did Lucy, separately. They met in Windsor, married, had six children before relocating to northern Michigan, where two more children were born. The small community thrived, as it does today. Lucy was successful in starting the first school and the Berry family holds an annual reunion.

— Pam Burris (aka, Palmer Ownschild)

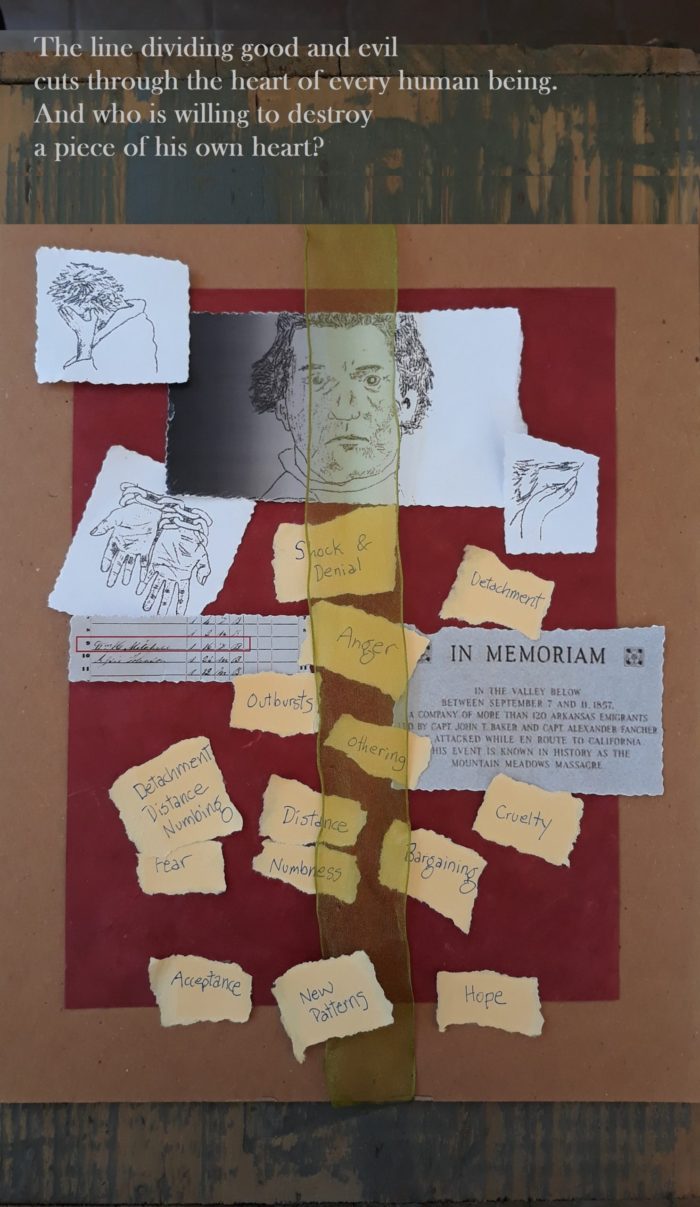

GRIEF HAS NO DIVIDING LINE

I grew up hearing about my grandparents sharecropping in the 1920s, so I always assumed my ancestors were poor. But then I learned that I had a few ancestors who had enslaved people. I felt the shock, horror, and dismay that every white person feels when they hear something like this. I knew my family could be cruel (in the name of “building character”), but I also felt a sense of betrayal. Why hadn’t someone told me before now? And why hadn’t they been better people? But blaming goes nowhere, so I focused on learning more. I started with William Christmas Mitchell (William C), because I’d heard stories about his daughter-in-law, Granny Mitchell; “the mean Granny” who would roll up her apron and swat my grandmother with it, for no other reason than just because she was mean, so I was told.

I loved my grandmother despite her own meanness, and was torn between horror and love for my ancestors, for my own grandmother, and both horror and gratitude for William C., whose survival gave me life. So, I wanted to explore his life and tell his story frankly, to own up to both his humanness and his inhumanity.

William C. was a subsistence farmer in northern Arkansas, near Missouri. He had 11 children, the 7th of which is in my line. But somehow, sometime before 1860, he enslaved a young Black woman only 16 years old. My heart chokes when I think of what he surely knew: that he would have increased his wealth by raping her and producing children. He imitated on a small scale what his wealthier neighbors were doing, at grievous expense to her.

For this collage, I held my eyes inches from my only photo of him, tracing over every line and plane. In my desire to understand him better, I explored the nuances of expression on his face, his posture, and how he held his hands. For the young woman he enslaved, I had no such luxury. I added a photo of shackled hands, for what was done to her. But what of her, herself? I added a Xerox of the line for her in the Arkansas census—that is all I know. I struggled to bring them both to life as individuals in my heart.

William C had his personal grief. In 1857, two of his adult sons and their families joined a wagon train for California. While in Utah, they were attacked by Mormons disguised as Native Americans, who killed all adults and children old enough to identify their assailants. The dead were buried in an unmarked mass grave, leaving 17 babies alive. An investigation was started over what was called the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and William C. was delegated to return the children to Arkansas. But the investigation was dropped for a more pressing matter: the Civil War.

William C. joined the Confederate Army, and was captured in the Battle of Pea Ridge. He was offered freedom if he would promise to stop fighting. He promised, and returned to Arkansas. He was in ill health when he arrived and died shortly after, before the war ended.

As I collage his image, my heart recoils when I think of what he did, and examine his face. In his slouching posture and defiant eyes, I see profound hardness. He had to have had profound numbness, hardness, and hard-heartedness to enslave a young woman, steal her life and her labor, and to rape her or even just to think of raping her. Did he ever feel the need to search for self-forgiveness? How do I reconcile his crimes? Or those of my ancestors whose stories I have not yet learned?

My heart also goes out to him when I think of his grief over losing his two oldest sons and their families in the Massacre, knowing their bodies lay in an unmarked grave while their attackers went free, and undertaking the heartbreaking job of gathering the babies and returning them to Arkansas.

And my heart aches for the young woman he enslaved. I don’t know her name, although I continue to search for it. I only hope she lived to be emancipated. I haven’t found a will; maybe none was written during the upheavals of War. She was not listed with the Mitchells in the 1870 Census. The only record of her is a single line in the 1860 Census: Age: 16, Gender: F, Race: B. What I do know is that she was human, able to feel and comprehend, like he was. She felt grief as he did, knowing that he was allowed by the law of the times to rape her and sell their own offspring for money.

My collage includes expressions of the grief of both of them, as well as the elements of healing from grief. Maybe they experienced some healing, or maybe they died before then. But the forming of this collage and retelling of their stories, however incomplete, is one of my steps toward accepting the facts, the pain, and the grief, and of breaking the silence, owning up, taking responsibility, creating new more hopeful patterns, and healing.

— Cindy Carroll

WAKE UP!

Waking up to the truth that I descend from significant enslavers was like an explosion for me. It shattered and fragmented my sense of self, history, worth and reality. Growing up in Colorado and California, I knew very little about my mother’s deep Virginia and Tennessee roots. She left at a young age and rebelled against her conservative family by living a very different lifestyle than they approved of. Before she died, I received a copy of her paternal line’s family genealogy book, but never paid much attention to it. Until age 54, in January of 2020, I deeply believed the South, racism and enslavement, land theft and racial violence had absolutely nothing to do with me. And then I saw my first “slave schedule” and learned within a few hours that my mother’s direct paternal ancestors were responsible for the enslavement of over 280 people in Virginia, another 121 by great-uncles, and her direct maternal line in Tennessee enslaved at least 148 people, and an additional 455 if I count a single great-uncle. I’m certain there are hundreds more.

My collage shows the shrapnel hurtling outward, with the glittery green and purple foam cubes at the periphery representing my children, the future, and hope. My intention is to continue to wonder, process, grieve, rage, learn, and take action, all while discussing much with my adolescent children, allowing them to know the truth of who our family is from a much younger age than when I learned. They will continue to shine a light on the truth and transform this legacy.

Each section of the collage allowed me to explore a different aspect of this journey, to use words cut from magazines to express what often feels indescribable and complex. I’m at the center, and one path I captured has to do with my tyrannical brain and the white supremacy culture characteristics that often run me. The first year of this work, so much was in my head, and there were loud punishing voices driving me, not allowing me to rest or digest the horrors and vile facts I continued to uncover. It still takes over if I let it, but I’ve gotten better at catching it sooner and slowing down. There was urgency, right/wrong, perfectionism, obsession, and I tried to outrun my deep discomfort and grief by staying in my head and shaming myself when I longed to briefly pause my research and be kinder to myself. That is reflected in the collage. And “monster” refers to my own brain, as well as my specific enslaver ancestors. When I later allowed myself to get into my body, slow down, have compassion for myself, eat, hum, rock, breathe, and connect with others on this journey, I had more stamina and wasn’t so horrible to myself and my loved ones. Digestion is happening. Resiliency is building. Another path captures my feelings around the sacredness of this work, the magic I’ve seen when spirit guides me towards a certain clue, document, resource or person, and the deep commitment I have to this work and repair. Dreaming, stillness, trust, embracing mystery and ancestral guidance are here, along with the continued grief, disgust, anxiety and fear. It’s all here, the explosion and contradictions, in my head, in my psyche, nervous system, genetics, heart, breath and bones. It’s been here all along, just tightly wrapped up in secrecy, lies, shame and omission. It was like a pressure chamber, filling up, being passed down through the generations as shame, violence and addiction, never being faced, facts and reality buried and ignored. Until it had to be released, set free, given light and air, and much of it is still percolating up to the surface. I hope it never stops. It’s unbound now, and as the energy of an explosion ripples out, the shockwaves keep coming, and a new path forward (and connecting back) is cleared.

— Libby Floch

Each family story is honest and exceptional reading! Thank you for posting your personal inner feelings about the legacy of your family histories! Antoinette

Thank you to each of the artist storytellers for the depths and wisdom of what you have shared. This level of candor and reflection heartens me, gives me energy and courage for moving ahead through difficult family histories. Thank you.

Both the collages/artworks and the narratives are so wonderful, so moving, so evocative of all the complexities that go along with discovering our histories as descendants of enslavers. I was nodding along with so many phrases, describing the emotional impact of various discoveries. Thanks for doing all this hard work, inspiring the rest of us–or at least me!–to continue our own journeys.

Thank you, Margaret, for your supportive words, and for being on this journey with us.